The Subtraction Test isn’t a mental model in itself, but it relates to one: genre. Given some corpus of texts, a genre is a pragmatic class of some members in that corpus—that is, texts don’t innately belong to a genre, but we organize them (a posteriori and inductively1) into learned genres because it’s analytically useful to do so.

Genres are hazily, even personally, defined; Genre Theory aims to explain why some things belong and other things don’t. Rick Altman imagines an illustrative argument about musicals:

A: I mean, what do you do with Elvis Presley films? You can hardly call them musicals.

B: Why not? They’re loaded with songs and they’ve got a narrative that ties the numbers together, don’t they?

A: Yeah, I suppose. I guess you’d have to call Fun in Acapulco a musical, but it’s sure no Singin’ in the Rain. Now there’s a real musical.2

Altman goes on to decompose film genre features into syntactic features (structural elements, like that a Western involve a governmental frontier, whether that be the borders of a town or some intergalactic outer limit) and semantic features (characteristic symbols: dust and dusters for the Western, song and dance for the musical, and so on). I like this breakdown for film—syntaxes link apparently distant texts—but it doesn’t generalize to the genre mental-model.

We can make Altman more generic by setting aside the feature categories (syntactic and semantic).

Suppose we have a genre G. The simplest definition for the genre would be to decompose it into a complete set of necessary features {f1, f2, …fn}, where every feature must exist in a text T if it’s to be included in the genre. That is, T ∈ G ⇔ {f1, f2, …fn} ⊆ the features of T.3 Using this to filter texts gives us the “inclusive list,”

an unwieldy list of texts corresponding to a simple, tautological definition of the genre (e.g., western=film that takes place in the American West, or musical=film with diegetic music).4

The inclusive list is unwieldy because it doesn’t leave much room for nuance, e.g. to say that casting Elvis makes something less characteristic of the musical genre. We can complicate the definitions by adding unnecessary features and weighting them,5 but that gives us unwieldy definitions and a false sense of precision.

When I say we learn genres inductively, I mean we learn the genre holistically: rather than accumulating a set of atomic features {f1, f2, …fn} that characterize a cluster of texts, we learn a genre duck test: “if it looks like a [musical] and quacks like a [musical], it’s a [musical].” Formally, a test function duckG(T) → {true, false} returns true if and only if the text T belongs to the genre G.

A Subtraction Test (my invented term) is a way of revealing relationships between particular features of a text and the genres to which the text belongs.

Imagine decomposing a text T into its features: T = {t1, t2, …tn}. Subtraction-testing means comparing duckG(T) and duckG(T\{ti}): does removing the feature ti change whether the text is a member of G?

| duckG(T) | duckG(T\{ti}) | Implication for G | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| true | true | ti is not necessary. | High Noon without revolvers is

still a Western. ∴ a Western needn’t include revolvers. |

| true | false | ti may be necessary. | Annie without musical numbers is

no longer a musical. ∴ a Musical may need musical numbers. |

| false | true | ¬ti may be sufficient. | I don’t know, can you think of one? |

| false | false | ¬ti is not sufficient. | No Country for Old Men without

milk is still not a musical. ∴ milklessness does not a Musical make. |

Note how the implications are qualified: subtraction tests are confident when subtracting a feature does not impact a text’s classification. When the classification changes—either from true → false (indicating necessity) or from false → true (sufficiency)—we learn something about the directional influence of the feature but can’t make too strong a claim. Maybe you don’t think Star Wars is a Western, but you imagine it’d pass if it didn’t have the space travel; that means you think space travel makes a film less Western-y, but it obviously doesn’t mean every space-travel-free film is a Western: Annie ain’t.

Notably, this works for multi-feature sets as well as single features: we can check duckG(T\{ti,tj}). Nothing guarantees that our features contribute independently to genre membership—rolling papers signify differently in front of a Bob Marley poster and in a gumshoe’s breast pocket—but I rarely think about independence. If you’re designing Taguchi experiments, either you’re deep in the realm of false precision or your inductive categories are already sophisticated.

I’ve been leaning on films because they’re popularly associated with genre, but the model and test are portable to other informal clustering activities. Do you cluster inbound support tickets to prioritize product improvements? Pinning down litmus tests for whether a new ticket belongs in a certain cluster means you can share the task with a person who would naturally cluster differently.

We learn duck tests for informal categories all the time; Subtraction Tests inch usefully towards formalism.

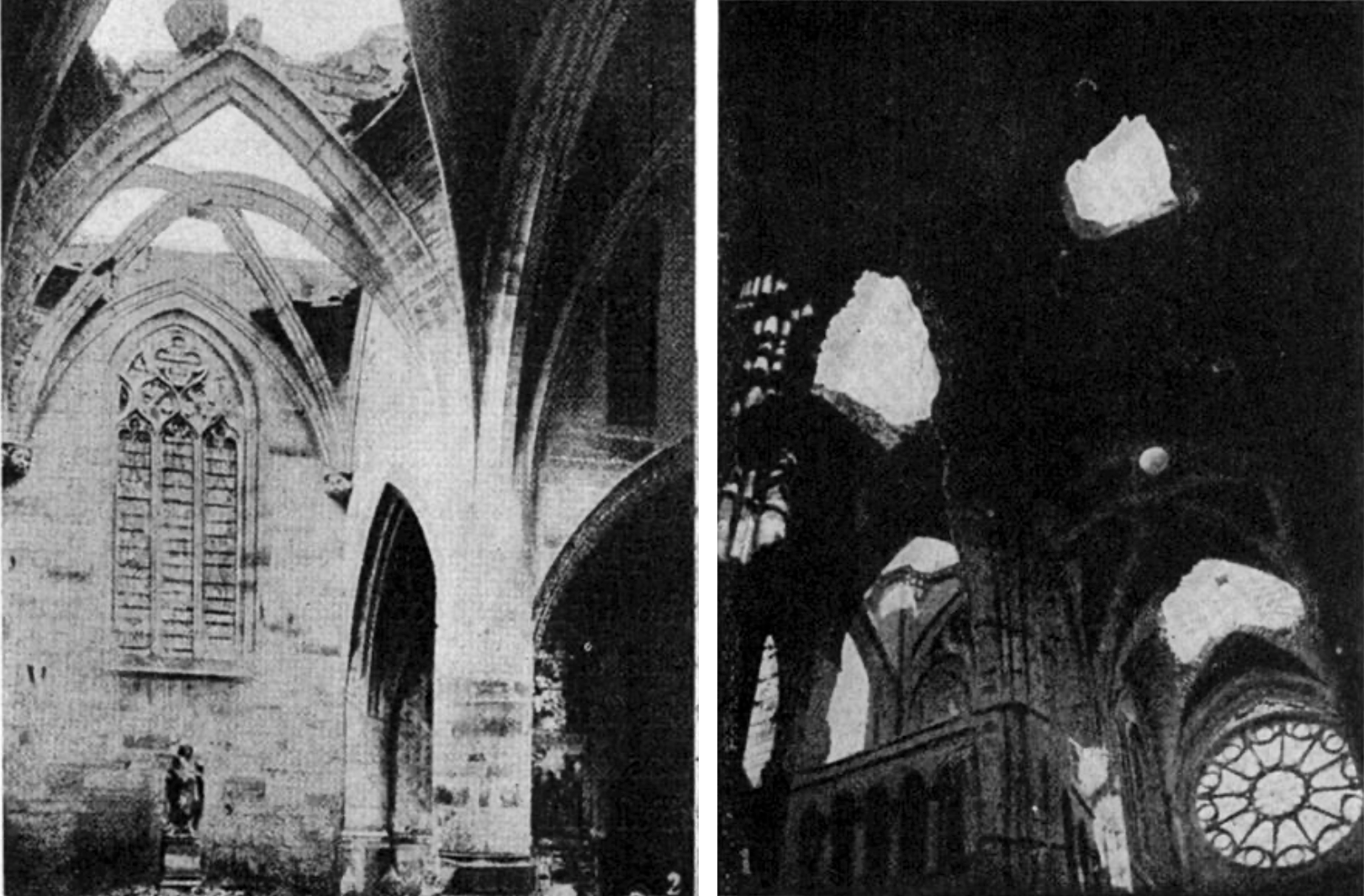

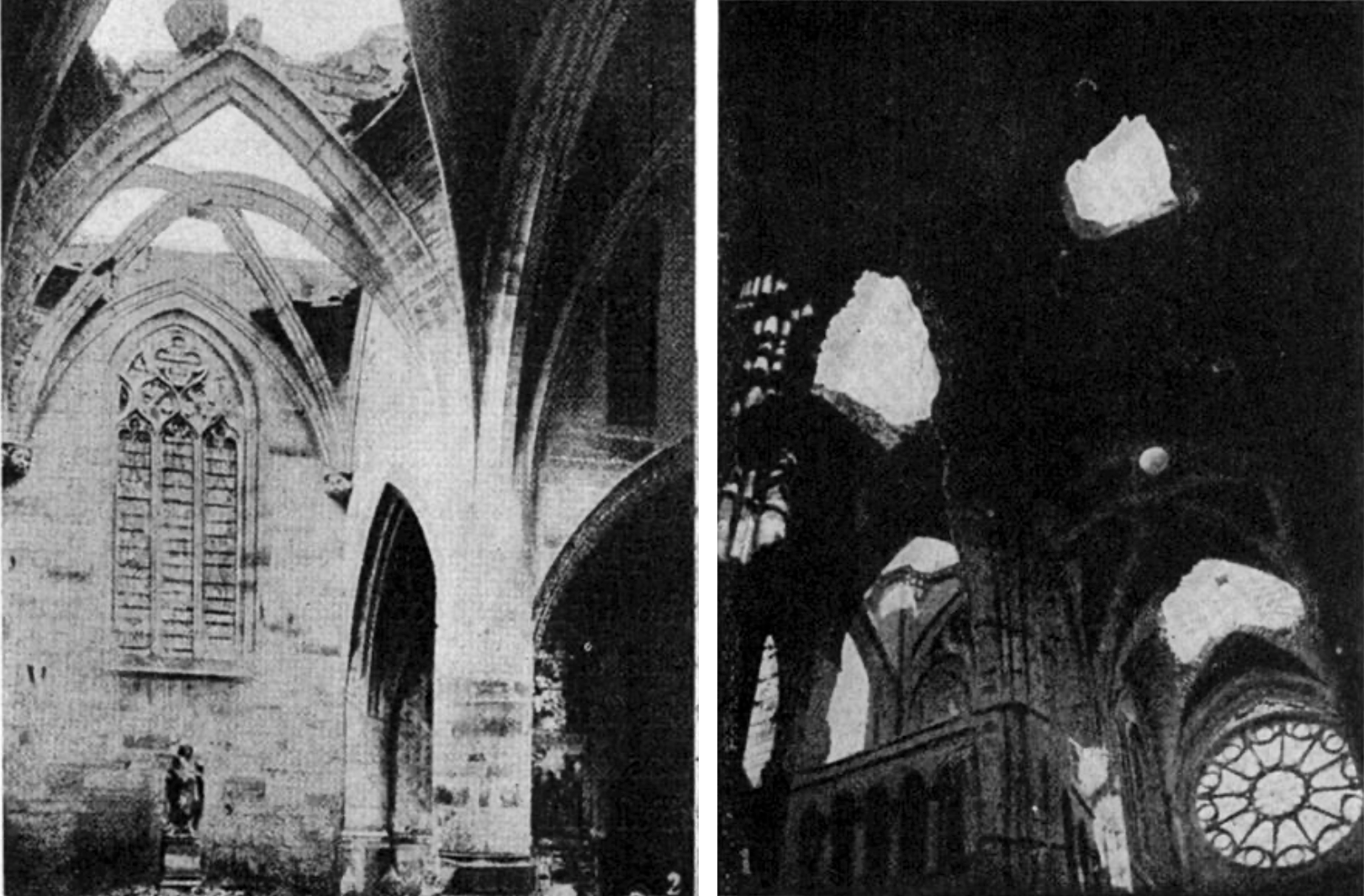

Caution: not everything that looks and quacks like a Subtraction Test is one. I’m only writing any of this down because Gilman’s The Theory of Gothic Architecture and the Effect of Shellfire at Rheims and Soissons6 falsely reminded me of Altman’s Elvis example. Gilman, writing in 1920, discusses gothic cathedrals damaged in World War I. The War did the subtraction for him, so he needn’t imagine structures without features: where artillery removevd a particular feature, Gilman considers whether the damage cascaded (e.g. in a collapse), which would indicate that the feature was structurally necessary.

Structurally unnecessary features, he reasons, are expressions of a gothic architectural ideal unmuddled by the cathedral’s physical pragmatics. The style is purest-expressed in the ornamentatal, and Gilman’s contemporaries debated whether gothic cathedrals revealed their true structures, which might’ve otherwise been hidden, or whether the cathedrals were ornamented with faux-structure—piers that support nothing, decorative buttresses, and so on. Gilman concludes the cathedrals are sometimes honest—

Closely connected with the principle of logic is that of revelation of structure for esthetic effect. Here again the ruins generally illustrate the theory and confirm it in its broad application. In the vaulting, the manner in which the breakage has occured, as well as its extent, does confirm strikingly the theory that the ribs carry the vault cells and are not only real functioning members, but are the most important part of the vault.7

—and sometimes not:

Now actually we find that some of the cases often considered as revealed structure are not the real structure. At Soissons the single shaft on the lower story of the nave piers does not really support the vaulting shafts and, in turn, the vaults above […] It by no means follows that the shaft is not good design, only that it does not express the facts of this structure; it is in fact an eye-satisfying fiction, although perhaps, a proper one.8

The first sign that Gilman’s treatment of subtraction and genre differs from our Subtraction Tests is that subtractability leads Gilman to the opposite conclusion. In the damaged cathedral, that “the single shaft on the lower story of the nave piers does not really support the vaulting shafts”—that those single shafts are subtractible in Gilman’s sense—means we should consider them a purer reflection of a gothic architect’s ideal. That’s very different from concluding “ti [the lower story of the nave piers] is not necessary” for a building to be gothic; that may be true (a feature can be characteristic without being necessary), but seeing a cathedral sans piers doesn’t give us evidence to that effect. It doesn’t even mean the feature is insignificant to the genre: that an architect chose a nonstructural pier rather than a nonstructural doric column makes the building more gothic, not less.

The key difference is that Gilman isn’t applying a duck test. When he sees a partially destroyed vault, he asks not “is this still gothic?,” but “is this still standing?” He isn’t comparing whether the building’s genre status changes, and he gives no reason to believe it does (a building may go from “gothic cathedral” to “gothic semi-ruins,” but nobody thinks it stops being gothic).

Gilman’s subtractions tell us about architectural intent—choices to build structurally unnecessary elements, despite their difficulty and expense—not about necessity and sufficiency to his architectural category. Be careful that your duck test is, in fact, a duck test.

Is “gothic” a genre? The category certainly developed a posteriori and inductively. Its builders were aware of their style, but I haven’t read any indication that they were self-awarely participating in a break from the sacred architecture that came before them. To the contrary,

The architect who built the choir of St Denis must have spoken to Suger about the arcus in the vaults; William of Sens in speaking to the Abbot of Canterbury no doubt used the term fornices arcutae, and Villard de Honnecourt probably spoke to his apprentices of Ogives. However, no name for the style itself is known to have existed at this time; indeed, it is unlikely that any name did exist, for, in the regions where the Gothic style was born and developed, ‘building in the Gothic style’ was simply called building.10

“Gothic” was only identified as a genre, with common architectural elements and decorative tendencies, in retrospect (typical: we have to find noncontemporary names for yesterday’s “modern”):

When in the course of the nineteenth century historical knowledge of the birth of the Gothic style, its development, and its spread increased, the Late Gothic style was still regarded as part of the Gothic style. Moreover, the growing study of the essential Gothic elements, beginning with Wetter’s book, and the attempts to interpret the essence of the Gothic, which began with the work of Viollet-le-Duc, and have continued to our own day, have neutralized the effects of personal taste and have led to a more intensive analysis of the concept of Gothic style.

The scholarly consideration of the Gothic style began with descriptions of individual buildings and so came to the study of individual members, such as pointed arches, piers, rib-vaults, windows, doorways, roofs, and towers. At the same time a desire grew to understand the essence of the Gothic style which could permeate such divergent features as piers and windows. The Gothic style was said to possess a picturesque quality, a quality of infinity, a vegetal quality, a romantic quality. All these different concepts were first formulated in the eighteenth century and were then considered more closely in the nineteenth and systematically bound into one unified concept.11

Interestingly, the genre-awareness of 19th-century restorationism means “restoration” may be a misnomer for what Viollet-le-Duc went about doing. Viollet-le-Duc was widely criticized for intervening ahistorically in the buildings he restored, emboldened by his conclusions about the driving principles of Gothic style, including scrubbing them of historically authentic, if post-gothic, features. Perhaps the very notion of a unified principle is fraught: even the individual cathedrals in Voillet-le-Duc’s canon were constructed over the courses of centuries. Should we believe these principles stayed fixed over several generations of builders?

Incidentally, Frankl also offers a better term than Gilman for style expressed in the structurally unnecessary, a “margin of freedom:”

In other words, function always leaves a ‘margin of freedom’ which cannot be resolved by utilitarian considerations and which is not objectively pre-determined. […] Gothic vaults must be examined in the light of their function; […] even when these functions have been understood, the question as to why these mebers have so many different profiles in different churches still remains unanswered, since each profile fulfils the necessary static function, in so far as it exists equally well.12